Thought Pieces / Jun 26, 2020

Framing COVID-19 Topic #13: Framing for as long as it takes

Framing COVID-19

Topic #13: Framing for as long as it takes

Daily events may seem unpredictable right now, but they reflect long-standing issues. Coronavirus is new, but the challenge of protecting public health and eliminating health inequities is not. Each new incident of anti-Black violence is a fresh injustice, but the history of racism and white supremacy reaches back for centuries.

As advocates for social change, we must engage in the conversations of the day while also taking the long view. Our voices and perspectives are vital right now in shaping a just recovery and a just society. At the same time, we know that major change doesn’t come overnight, and it doesn’t come from our efforts alone. While change can sometimes seem to sprout quickly, it emerges only if the right seeds have been planted and the ground is fertile. And it only continues to grow if carefully tended.

For the future we want to take root, we must continuously cultivate our frames, appreciating the progressive ideas that others planted long ago and growing the narratives that need to flourish across generations. Here are three ways we can sustain our efforts to reframe social issues.

1. Put your ideas on repeat—without sounding repetitive.

For our ideas to break through and take hold during the noisy time ahead, we need both discipline and inspiration. Repetition is essential—one of the most powerful predictors of whether people believe something is the number of times they’ve heard it. But if we sound scripted, we seem inauthentic and lose credibility. The best way to manage this tension is to be good storytellers, bringing our same fundamental frames to life in fresh ways each time.

When new communications opportunities and challenges arise, we can turn to trusted, effective frames. This means showing what’s at stake by consistently expressing motivating values rather than expecting stark statistics to motivate and move people. It means returning, again and again, to core explanations instead of splintering our stories by looking for a novel response to each new development.

As we commit to being consistent, we must also commit to being creative, finding ways to refresh and revive our enduring frames. We can invite new voices to share their version of a movement’s core story. We can express our values in unexpected ways; look for new images to illustrate our issue; find timely examples of a timeless theme.

For inspiration and insight into how an enduring frame can be expressed in multiple ways across time, look to the example of how the value of human equality has been communicated across the past century and a half:

1867: Sojourner Truth’s address to the first annual meeting of the American Equal Rights Association

“If it is not a fit place for women, it is unfit for men to be there.”

1948: Universal Declaration of Human Rights

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

1963: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s address at the Freedom Rally in Cobo Hall

“We want all of our rights, we want them here, and we want them now.”

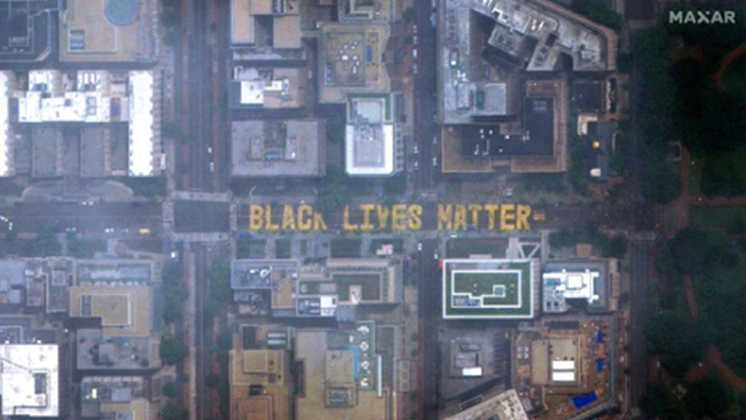

2020: Satellite view of Black Lives Matter mural painted on the DC street in front of the White House

2. Be prepared for what we can predict.

We can anticipate some of the framing challenges that lie ahead. Through the crisis and on the long road to recovery ahead, when things are bad, we’ll be told they can’t be any different. We’ll hear voices that fuel division and hostility. And we’ll encounter the idea that since there isn’t enough to go around, tough choices must be made and some needs can’t be met. These frames undermine the very idea of a more inclusive, more equitable, and more sustainable future.

We need to be prepared to disrupt these toxic narratives—not by rebutting (and repeating) them but by offering a compelling alternative.

To avoid activating fatalistic thinking, we need to communicate that change is both possible and feasible. This kind of framing doesn’t deny that problems exist; it emphasizes that they can be solved. We can turn to strategies that have worked to counter fatalistic thinking on housing, hunger, and homelessness.

To dampen Us vs. Them thinking, emphasize our shared fates. We can highlight our interdependence and our mutual responsibilities to each other. We can learn from approaches that have worked to redirect Us vs. Them thinking on aging, human services, and immigration.

To disrupt Zero-Sum thinking, it’s important to shift the underlying assumption that resources are fixed and finite. It helps to find ways to show that resources are dynamic and changeable. We can adopt framing techniques that countered Zero-Sum thinking on the economy, learning and linguistic diversity.

3. Center people’s needs and voices, but always show context and connections.

To gain support for people-first recovery polices, we must foreground people’s needs—for wellbeing, for security, for dignity—and talk about how collective decisions affect those outcomes. The experiences of people affected by policy decisions are important and powerful contributions to the conversation. But the way stories, experiences, and voices are presented is also enormously important.

We have a built-in tendency to attribute the outcomes of a story to actions of the main characters in it. This makes it easy for us to see happy endings as the result of individual willpower and to blame hardship on bad choices.

Just as we can’t expect a stand-alone statistic to tell a whole story, we can’t expect a personal story to illustrate every dimension of a broader issue. To avoid having our personal stories activate judgment or perpetuate stigma, we need to include signposts that point people to the meaning we hope they’ll take away.

To do this, we can tell stories of people’s lived experiences in ways that explicitly signal shared, widespread conditions. We can identify root causes when we highlight unacceptable effects. And we can point to social context—clearly showing where sources of support were available or where they were absent.

To see how to make systems and circumstances central characters, not forgotten plotlines, explore these examples of personal stories on , poverty, and elder abuse—and notice the strategies that reveal systemic contexts.

About this series

This concludes our special series on framing during the pandemic. We hope you have found value in these ideas. You can revisit them in our Framing COVID-19 Archive at any time.

But our efforts to respond to this moment are not over. We’ve launched a major research project to track changes in public thinking on social issues in the era of COVID-19 and to find ways to frame the need for change.

Issues: Evidence-Based Policymaking, Health